(1) Gravitational Wave Events

a. Kilonovae

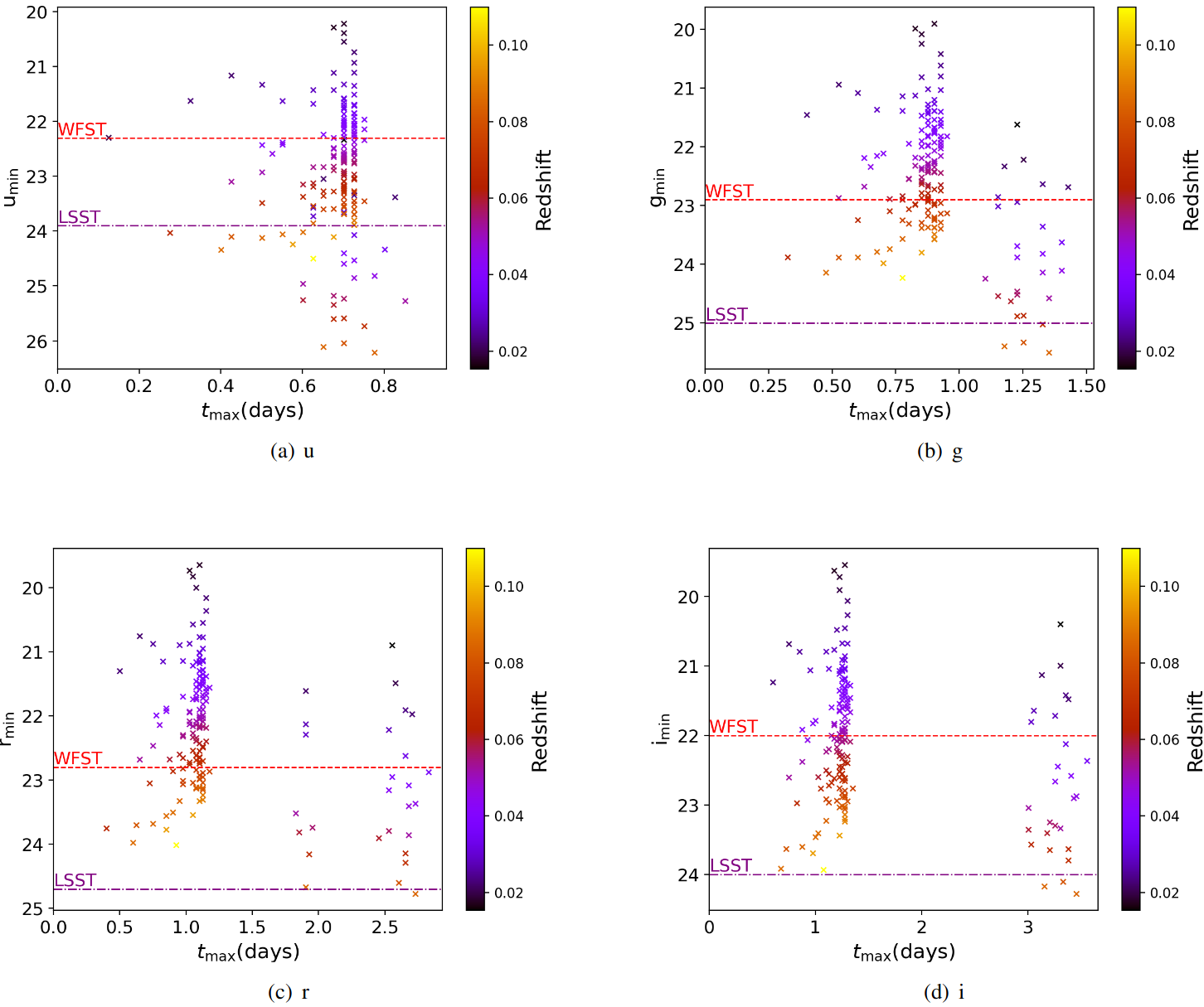

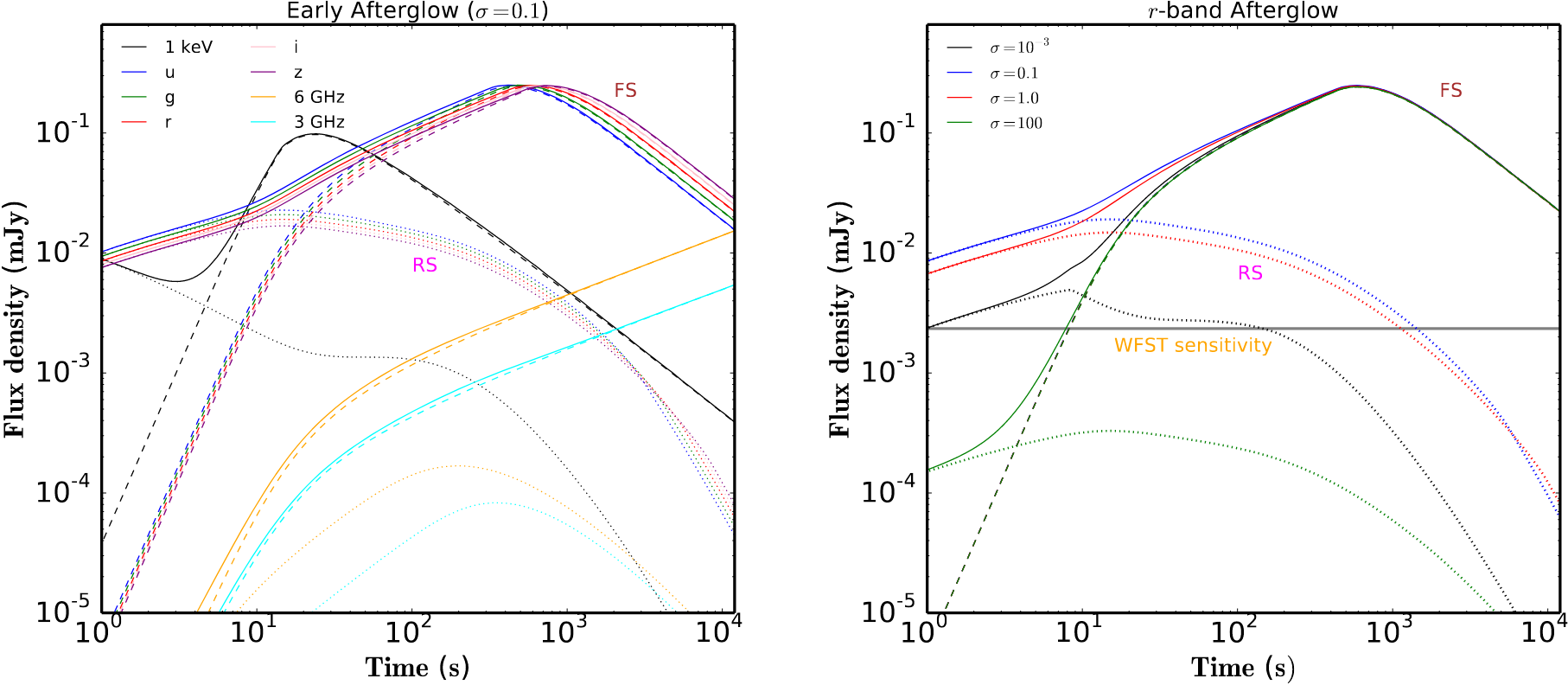

In Figure 1, we illustrate the peak luminosity magnitude and corresponding timing for kilonovae resulting from Binary Neutron Star (BNS) mergers that are detectable by the Laser High-Vacuum (LHV) observatory with a Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) exceeding 10. In each panel, two dashed lines represent the single-visit depth achievable with a 30-second exposure using the Wide-Field Space Telescope (WFST) and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST).

It's important to note that the redshift limit of LHV is approximately 0.12, while WFST can effectively observe kilonovae up to a maximum redshift of around 0.06 in the r-band. The i-band panel illustrates that the time of peak luminosity typically falls within a concentrated range of 1 to 3 days. This phenomenon is a consequence of the mass ratio between the two neutron stars involved in the merger. In cases where the neutron stars have unequal masses, the less massive neutron star is tidally disrupted before direct contact. This results in the suppression of shock production and the "blue" components of the kilonova. On the other hand, the "red" component, characterized by higher opacity, takes a longer time for its photons to diffuse. As a result, kilonovae dominated by the "red" component reach their maximum luminosity at a later time.

Observations in the i-band allow for a more profound understanding of the color evolution of kilonovae and the nature of the ejected material. Additionally, it's worth noting that the u-band luminosity reaches its peak within a few hours. Past observing campaigns, such as the one for AT2017gfo, lacked u-band imaging. Hence, a rapid u-band search using WFST can facilitate investigations into the early hours of kilonova evolution.

Table 1 provides information on the expected number of BNS mergers with observable Gravitational Wave (GW) and kilonova signals per year. This estimation is based on assumptions including a local BNS merger rate ranging from 80 to 810 Gpc^(-3) yr^(-1), a survey area covering approximately 50% of the entire sky each night, and a fraction of around 70% of nights being suitable for observations. The results indicate that WFST and LHV are expected to detect approximately 1 to 13 multi-messenger events per year in the g- and r-bands, with slightly lower rates in the u and i bands. The z-band, due to its relatively lower sensitivity, is likely unsuitable for kilonova searches.

The plan is to prioritize u- and g-band campaigns, particularly focusing on the first few hours of kilonova search. Subsequently, the observations will shift to r- and i-bands, with a special emphasis on optimizing the search efficiency for red kilonovae.

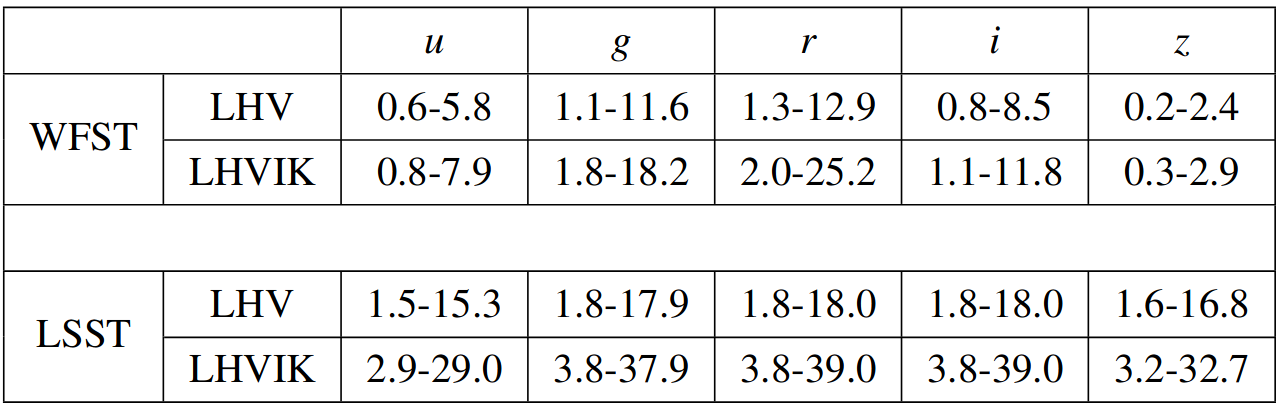

b. Gamma-ray bursts and afterglows

In the context of high-redshift events, the Wide-Field Space Telescope (WFST) is expected to detect electromagnetic (EM) counterparts, primarily in the form of short-duration Gamma-ray Bursts (sGRBs) and their afterglows. To identify suitable candidates, we consider Binary Neutron Star (BNS) samples that can trigger both Gravitational Wave (GW) interferometers and gamma-ray detectors, using the GECAM result as a reference. In Figure 2, we present the distribution of redshifts and inclination angles (ι) for these BNS systems. The corresponding r-band magnitudes are indicated by the colorbars in Figure 2.

We proceed to estimate the afterglow magnitudes in the r-band using standard afterglow models. Our calculations demonstrate that the considered afterglows are all detectable by WFST. However, when we account for factors such as the fractions of observable sky area and observation time, we find that the joint observation rate of sGRBs and their afterglows is expected to be less than approximately 2 events per year. This rate is notably lower than that expected for kilonovae. Consequently, our WFST search programs for GW EM counterparts will primarily focus on kilonovae.

c. Optical counterparts of other GW events

Kilonovae and optical afterglows resulting from Black Hole-Neutron Star (BH-NS) mergers represent another class of multi-messenger sources that we anticipate discovering using the Wide-Field Space Telescope (WFST). In scenarios where a primary BH with a high-spin distribution merges with a less massive NS companion characterized by a stiff Equation of State (EoS), it is expected that the NS will be disrupted by the BH in nearly every case. This disruptive process generates significant energy, leading to the emission of a bright kilonova and an afterglow.

While it is challenging to provide a precise quantification of the detection rate for optical counterparts associated with these Gravitational Wave (GW) events due to the intricate parameter dependencies involved, an optimal estimate suggests that WFST may detect such optical counterparts at a rate on the order of approximately one event per year.

To address the complexities and uncertainties in determining the detection rate for optical counterparts in these GW events, the GW-triggered target-of-opportunity observations carried out by WFST will play a crucial role in shedding light on the formation and evolution of these events.

(2) Gamma-ray Bursts

a. The Early Optical Afterglow

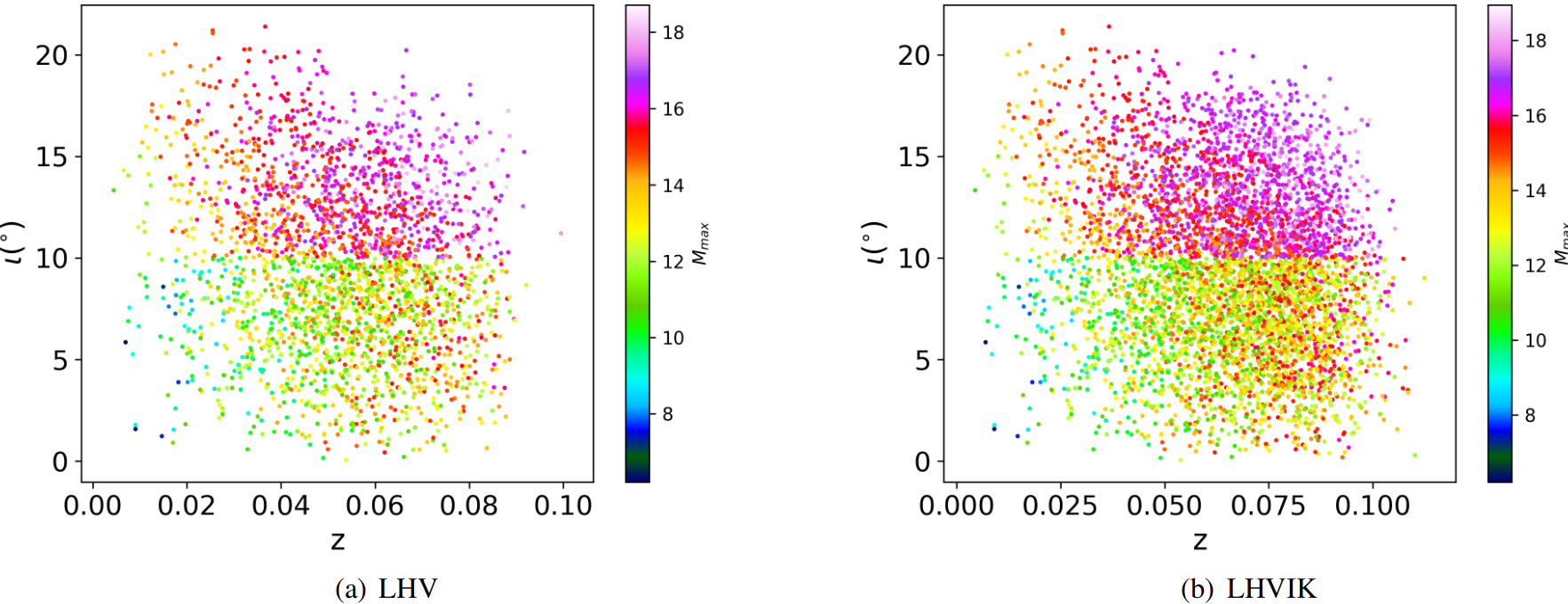

Conducting a wide-field survey of Gamma-ray Burst (GRB) optical afterglows holds the promise of significantly increasing the number of early optical afterglow observations, thereby enhancing our comprehension of GRB jets. Figure 3 presents a collection of numerical multi-wavelength light curves from the Forward Shock-Reverse Shock (FS-RS) system. These curves illustrate how the emergence of RS (Reverse Shock) emission can result in early-stage light curves that deviate from those expected in a simple external shock scenario.

Our findings indicate that RS emission plays a substantial role when the magnetization parameter (σ) of the GRB ejecta falls within the range of 0.1 to 1, dominating over Forward Shock (FS) emission. This occurs because, in the early stages, a weak magnetic field inhibits synchrotron radiation for σ << 1, while a strong magnetic field weakens the RS itself for σ > 1. Consequently, the observation of a significant number of early afterglows will provide valuable constraints on the σ parameter for GRB jets on a statistical basis.

Within the context of our WFST surveys, the sensitivity limit is comfortably below the early RS flux of a typical GRB, and the Field of View (FoV) can encompass the uncertain region of the GRB location within several pointings. This demonstrates WFST's capability to capture early afterglows.

On average, Fermi/GBM reports approximately 300 GRBs per year, with at least 10% falling within the survey area of WFST (considering site conditions and the fraction of observable nights). We plan to observe the targets with a position uncertainty of less than 10 degrees, corresponding to around 37% of the total. Using a 30-second exposure for each pointing, our simulations indicate that for these target candidates, there is roughly a 22% chance of capturing the rising phase of the early afterglow. Consequently, we expect WFST to detect approximately 2 to 3 "golden" early afterglows annually.

Furthermore, the SVOM satellite, scheduled for commissioning in 2024, is expected to report approximately 70 GRBs with a localization error of around 10 arc minutes. This would result in a higher WFST detection rate of roughly 7 golden early afterglows per year, offering a more optimistic outlook.

b. High-redshift Gamma-Ray Bursts

To leverage the potential of Gamma-ray Bursts (GRBs) as a cosmological tool, it's imperative to assemble a larger sample of high-redshift (high-z) GRBs. However, high-z GRBs present a unique challenge because their optical afterglows fade rapidly, often becoming too faint for redshift determination within a few hours. The key to addressing this challenge lies in coordinating worldwide efforts to follow up on GRB alerts.

The Einstein Probe (EP) plays a crucial role in this process by distributing timely alerts, enabling the orchestration of follow-up optical campaigns. In this context, we anticipate that WFST will make valuable contributions by providing follow-up multi-color images, which facilitate photometric redshift estimates for high-z GRB candidates.

During the EP era, the combination of rapid visible/NIR photometry using WFST and subsequent deep spectroscopic measurements using larger ground-based telescopes will establish an efficient pipeline for the identification of GRBs at redshifts greater than 6. This approach will not only expand the high-z GRB sample but also enhance our understanding of the early universe.

(3) Fast Radio Bursts

A central question in the study of Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) revolves around their origins. Specifically, researchers are keen to determine whether all FRBs stem from magnetars associated with Core-Collapse Supernovae (CCSNe). Moreover, there is considerable interest in understanding whether repeating FRBs and apparently non-repeating FRBs share a common origin.

To address these compelling questions, WFST surveys are anticipated to play a crucial role, particularly by examining the host galaxies of FRBs and studying their optical counterparts. These investigations will shed light on the origins and characteristics of FRBs, helping to unravel the mysteries surrounding these intriguing astrophysical phenomena.

a. Host Galaxy

The similarity observed in the host galaxies and sub-galactic environments of Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) suggests a potential association between FRBs and other transient phenomena. Currently, there are 18 identified FRB host galaxies, hosting 7 repeating FRBs and 11 apparently non-repeating FRBs. However, the limited sample size presents a significant challenge for conducting in-depth investigations, making it difficult to discern between the proposed models for the mechanism and origin of repeating and non-repeating FRBs.

The deep imaging capabilities of WFST in the northern hemisphere are expected to provide valuable insights into the host galaxies of FRBs. To assess the feasibility of distinguishing between repeating and non-repeating FRB host galaxies, researchers have expanded the sample size to 72 by resampling known FRBs. They have conducted Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests on various host properties, including stellar mass, star formation rate (SFR), specific star formation rate (sSFR), and the galactocentric offset of the FRBs. The results indicate that the probability of repeaters and non-repeaters being drawn from the same sample is less than 0.05.

Based on these findings, it is concluded that with a larger FRB host galaxy sample made available through the deep imaging capabilities of WFST, along with an expanded FRB sample featuring arcsecond-localization from future radio telescope arrays, it will be possible to differentiate between repeating and non-repeating FRBs, provided they have distinct origins.

b. Optical Counterparts

Theoretical models predict that the optical-to-radio flux ratio ην = fopt/ fradio of FRBs ranges from < 10−11 to 0.1 [136, 138, 139], and the optical radiation most detectable by WFST results from the inverse Compton scattering of FRBs inside a neutron star magnetosphere or an SNR, which typically yields ην = 5 × 10−5 and 10−4, respectively. Assuming an FRB to last 1 milli-second, the FRB fluence function from CHIME observations leads to the flux function N(> fradio) = 818+229 −210( fradio 5 Jy )−1.4 sky−1 day−1. The WFST detection rate of an FRB optical counterpart is thus estimated by N = NFRB(> fopt/ην) ∗ FOV, where fopt = tFRB,o fopt,30/tobs for a counterparts with a duration tFRB,o < 30s, fopt,30 is the 30s exposure r-band detection limit of WFST, and a 7 deg2 FoV is applied. As a result, the event rate of the ms optical counterpart produced by magnetospheric IC is estimated to be 0.02 yr−1, while the optical counterpart lasting for hours produced by FRB-SNR IC is 200 day−1 in an ideal case.

The result of WFST surveys will have profound implications to FRBs, because an unambiguous detection of their optical counterparts will open up a new window for this frontier, whereas no detection also delivers constraints to the present models.

(4) Optical Counterparts of High-energy Neutrinos

When particles are accelerated in an astronomical object (e.g. by terminal shocks), the interaction between the accelerated cosmic rays and the surrounding matter or target photons often produces high-energy neutrinos and photons. The electromagnetic counterparts of high energy neutrinos are instrumental to the identification of candidate neutrino sources, the determination of the distance to these sources, the exploration of their properties, and our understanding of the acceleration and radiation mechanisms therein, highlighting the necessity of searching for electromagnetic counterparts or transients in coincidence with neutrinos temporally and spatially.

Residing on the northern hemisphere and possessing a sufficient FoV to cover the area of angular uncertainty for most neutrino events detectable by IceCube in a single exposure, WFST will serve as an ideal follow-up optical facility. Meanwhile, the optical timedomain surveys by WFST will discover more SNe, FBOTs, TDEs, GRBs and AGNs, allowing cross-identification between the detected neutrinos (real-time or archival) and WFST’s legacy data. WFST surveys also promise to help identify neutrino sources and further constrain the acceleration mechanism of cosmic rays, the radiation mechanism of neutrinos, the redshift and other properties of the sources of scientific interest.